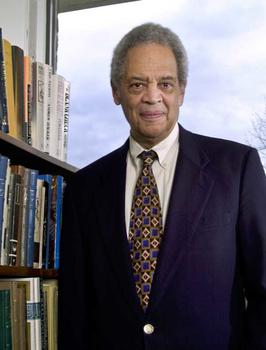

His schooling began in a one-room, segregated schoolhouse. Despite his humble beginnings, Roger Wilkins managed to navigate his way into the nation’s most powerful corridors while championing civil rights and helping America square the lofty words of its founders with their actions.

George Mason University formally honored Wilkins, a former Robinson Professor who died in March at age 85, by dedicating the Johnson Center North Plaza to the civil rights advocate and prize-winning journalist on Oct. 12.

The ceremony held added meaning for Patricia King, Wilkins’ wife of 36 years who grew up in a segregated Virginia.

“We are all so proud of Roger and so thankful you are recognizing him today in this extraordinary way,” she said. “I never thought I’d see a day like today.”

George Mason President Ángel Cabrera praised Wilkins for inspiring and shaping the thinking of “hundreds if not thousands of Mason students” during his tenure from 1986 until his retirement in 2007.

“When Roger came to George Mason, few knew much about this fledgling university in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C.,” he said. “Roger was one of those intellectual pioneers who helped put this university on the map.”

Joining Cabrera at the ceremony were Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post columnist Colbert I. King, other members of the Wilkins family and roughly 100 members of the Mason community.

Colbert King (no relation to Patricia King) lauded his longtime friend for holding America accountable to its constitutional ideals. Wilkins served Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson and helped pass the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He was also among the first African-American editorial writers at both the Washington Post and the New York Times. Wilkins’ powerful editorials about the Watergate scandal helped him earn a share of the Post’s 1973 Pulitzer Prize for public service.

Wilkins had long closely examined the conundrum created by the exalted words of the nation’s Founding Fathers like George Mason who preached of liberty while participating in slavery to deprive that very liberty to those of color and others.

Wilkins had noted the contradictions in his writings and his teachings. He also acknowledged the efforts of the Founding Fathers, who created a country where a black man from unpretentious beginnings could rise to counsel presidents at the White House. Wilkins was just 33 when he became the nation’s first African-American assistant attorney general.

Along the way, he consistently delivered the message George Mason put forth in the Bill of Rights, contending that the rights, freedom and liberty to pursue happiness must be available to all in every way and at every time, Colbert King said.

“Roger exercised the independence that he admired in George Mason and would not let the nation get by with denials,” he said. “Where would we be without Roger Wilkins? Wilkins, who helped us reconcile the beliefs of our founders with universal equality and their participation in slavery.”