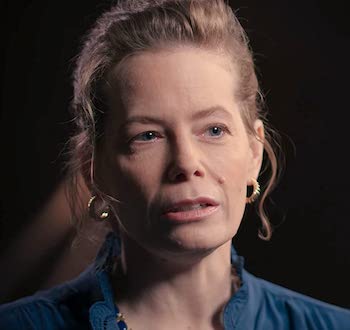

George Mason University Egyptologist Jacquelyn Williamson is the author of Nefertiti’s Sun Temple: A New Cult Complex at Tell el-Amarna, part of Brill’s Harvard Egyptology Series. She is involved in the ongoing archaeological investigation of Kom el-Nana at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt, the site of a sun temple associated with Queen Nefertiti. She teaches ancient art and archaeology in Mason’s Department of History and Art History. Currently you can see her in episodes of the new Netflix historical docuseries Queen Cleopatra. We recently sat down with her to talk about women and power in ancient Egypt.

How did you get involved with the Netflix series?

They reached out to me well over a year ago when they were still in the original planning stages. I think they were reaching out to several scholars. I'm not a specialist on Cleopatra, but I am a specialist on women and power in ancient Egypt. I've also done a little bit of work on the misinterpretation of Cleopatra in the modern day, which is basically based on Shakespeare's play, which is in turn based on anti-Egypt propaganda created by ancient Rome.

Could you expand on that?

Sure. Our modern perception of Cleopatra as this seductress is quite inaccurate. A lot of my work on Cleopatra is about what the ancient Romans did. They wanted to devalue Antony and Cleopatra for very specific political reasons, and they created “fake news” about them in order to promote their political agenda. Cleopatra was a human being, like you and I, she deserves the dignity of being represented as accurately as possible in the same way that you and I do.

Did you have to travel for the documentary?

I wasn’t involved in the planning of the production in any way. I was mainly a “talking head” and answered questions on camera. The American talking heads were shot at production studio up in Brooklyn, New York, which was convenient for me. Having it in Brooklyn made it a lot easier to fit to my academic schedule. This is a very elaborate and well-funded production. They paid for transportation and the hotel—and they actually had a makeup person on set.

I've been the talking head on a couple different documentaries before on ancient Egypt. For those, I was on site in Egypt, and that's just a small [production] group, just cameraman and maybe the onsite producer. [Queen Cleopatra] involved several cameras and a producer who was asking the questions for me to respond to. I had no input or influence on the casting choices, or on the drama/reenactment portions of the show. In fact, except for knowing the names of a few of the other academics they interviewed, I wasn't involved in any other aspects of the production. The series was not what I hoped, but then drama-documentaries almost never can live up to an academic’s dream as they always involve some creative license. Real history is often so wild and weird it is not helped by melodrama or modern political insertions.

Have you been back to Egypt since the pandemic?

Actually I have—I led a tour of Egypt with a Smithsonian Journeys group, but I haven't been able to get back to my archaeological site, which is the sun temple of Nefertiti. Leading a tour is very brief, about two weeks. To have real time on the archaeological site, I need at least three weeks, which is hard with my academic schedule.

What are you working on now?

I'm still compiling information for another book on Nefertiti’s sun temple at Kom el-Nana. In addition, I'm also working on a book project with my colleague Dr. Mariam Ayad [of the American University of Cairo] on women in Ancient Egypt. It's primarily a discussion of the misinterpretation of evidence about women in antiquity and the ways that we allow our modern assumptions and biases to kind of get in the way of analyzing that information. We have a tendency take women's stories and make them into things they're not. That does women an enormous disservice, which has been the fate of Cleopatra for 2,000 years. I am not sure whether this new documentary exactly helped advance the general knowledge of the real Cleopatra, but hopefully it made a few people curious enough to research her on their own.