Lee Talbot, 90, a professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy within Mason’s College of Science, died at home on April 27, 2021, following a battle with cancer.

“As an educator, Lee Talbot was both an inspiration and a pioneer, his passion and dedication to his students ever-evident over his 29 years at George Mason University,” said Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm, dean of the College of Science. “During that time, Talbot developed eight graduate-level classes and received countless student accolades and faculty awards, including the recent Dean’s Career Award for Distinctive Service in December 2020.”

A global ecologist and geographer with more than 50 years of experience in national and international environmental affairs, biodiversity conservation, management of wild living resources, environmental policies and institutions, and environment and development, Talbot is widely recognized as the author/co-author of the U.S. Endangered Species Act, Marine Mammal Protection Act, CITES and the World Heritage Convention. A senior environmental advisor to World Bank and United Nations organizations, he supported ecological research and advising efforts in 134 countries.

His former positions included, among others, chief scientist and foreign affairs director of the President’s Council on Environmental Quality for Presidents Nixon, Ford and Carter; head of environmental sciences for the Smithsonian Institution; director-general of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) t; member of more than 20 committees and panels of the National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council; and senior scientific advisor to the International Council of Scientific Unions. Over the course of his 50-plus year career, he conducted more than 130 exploratory and research expeditions to remote or unknown areas on five continents. Talbot wrote more than 300 scientific, technical and popular publications, including 17 books and monographs, with some translations in nine foreign languages. Talbot’s first book, published in England in 1960, was “A Look at Threatened Species,” and a majority of his subsequent publications addressed endangered species either directly or in the context of broader conservation issues.

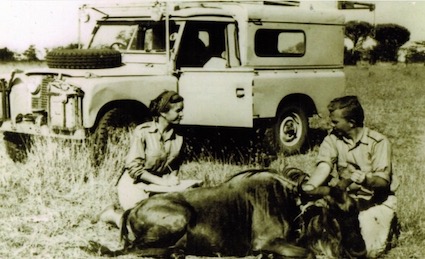

Beginning his career as a wildlife biologist on one of his earliest assignments, he mapped and collected data on animals in Kenya and Lake Tanganyika. The results were the creation of the Serengeti National Park, the Masai Mara National Reserve and much more. He and his wife, Marty, his co-adventurer, spent years assessing the status of species across Africa and Asia.

“If you want to know why species like tigers and gorillas and rhinos and African elephants are still roaming the wild, here’s why,” said Thomas Lovejoy, a noted conservation biologist and University Professor within ESP.

Talbot completed his undergraduate studies at the University of California Berkeley, receiving a degree in liberal arts and wildlife ecology, an MS in vertebrate ecology and an interdisciplinary PhD in geography/ecology. He also served in the U.S. Marine Corps.

After finishing his Marine Corps service in 1954, Talbot was asked to research African and Asian endangered species at the National Academy of Sciences, which led to the position of first staff ecologist of the Brussels-based IUCN.

“Talbot had three ‘true loves,’—his wife, Marty, and their family; exploring his passion for endangered species and conservation policy; and car racing,” said A. Alonso Aguirre, chair of Mason’s Department of Environmental Science and Policy. “Yes, Lee loved racing cars.”

Talbot was 18 when he was chosen to enter his first professional race in 1948, and 87 at the time of his final one in 2017. During that 69-year stretch, he enjoyed competing in—and frequently winning—a wide variety of vehicles and types of races, including dirt track sprint cars, dirt and ice rallying in production-based cars, and grand prix and road racing in formula cars, sports racers, production and vintage race cars.

“He was truly a towering figure,” wrote Talbot’s son, Russell, in a powerful tribute to his father. “I think of him as an amalgamation of the best aspects of John Muir, Ernest Hemingway, and James Bond. But I think he was humbler and, arguably, more influential than any of those characters.”

While teaching at Mason, Talbot mentored countless graduate students who are now spread out across the planet continuing his fight for sound conservation policy and development.

“We have lost a hero of the environment, but his impacts on species will likely extend far into the future because of his incredible efforts.” Aguirre said.

Marty, Talbot’s wife of 62 years, and sons Lawrence and Rusty plan to hold a celebration of his life in the coming months.