A new George Mason University study explores the complex connections between managerial feedback and creative outcomes.

The growing popularity of crowdsourcing and other forms of open innovation reflects the pressing need that companies have for creative ideas that go beyond the organizational same-old, same-old.

But once you have imaginative outsiders ready to lend you their time and attention, how do you elicit novel and useful contributions from them? It turns out to be as much about strategic communication as it is about the quality of your talent pool.

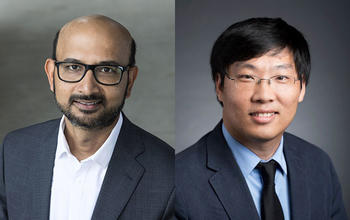

In recently published research, Pallab Sanyal, professor and area chair of information systems and operations management (ISOM) at Mason's School of Business, and Shun Ye, associate professor and assistant area chair of ISOM, focused on two types of feedback crowdsourcing participants commonly receive. Outcome feedback rates the perceived quality of the submission, with no underlying explanation (“This design is not good.”). Process feedback reveals or hints at what contest organizers are looking for (“I prefer a green background”).

Sanyal and Ye analyzed data from a crowdsourcing platform covering close to 12,000 graphic-design contests over the period from 2009 to 2014. The data-set included the contest parameters, time-stamped submissions and feedback, winning designs, etc. It also allowed the researchers to track the activity of repeat entrants from contest to contest across the sample.

This put them in a good position to measure how choosing one feedback type over the other affected contest outcomes—but not in terms of “quality” as it is traditionally defined by researchers.

“I gave a talk at a university where I showed 25 different submissions from a crowdsourcing contest and asked people to choose which one was the highest quality," says Sanyal. "And everyone in that room picked a different one. Not only that, the one that eventually won the contest was not picked by anyone.”

“The moral of the story is, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Whoever is the contest holder or client, whatever they think is best for their business objective, that is the highest quality.”

With this working definition in mind, Sanyal and Ye developed an artificial intelligence (AI) tool for scoring all submissions by visual similarity to the eventual winning submission.

“We use the algorithm to calculate the distance between these images and the highest-quality image, to give it a score, a quality score, between zero and one,” Sanyal explains.

They found that process feedback tended to increase the affinity of the designs, i.e., they were more similar to the winning design chosen by the client on average. By contrast, outcome feedback increased the diversity of the designs.

Sanyal and Ye theorize that precise guidance in the form of process feedback can lower ambiguity and assist competitors to narrow the search space, while outcome feedback expands the search space because it leaves plenty of room for interpretation.

Very late in the contest, though, the positive relationship between process feedback and submission affinity disappeared, and may have even flipped to the negative; the professors speculate this may be due to a demotivating, “now-you-tell-me” effect.

Shifting gears from quality to quantity, Sanyal and Ye discovered that both process and outcome feedback encouraged more submissions on the whole. However, they did so in different ways.

Process feedback lured new contributors to the contest; outcome feedback spurred more submissions per contributor. But, again, both of these effects were weakened when feedback was offered late in the game. Interestingly, this contradicts previous studies, which suggest early feedback discourages new contributors from joining. Shun and Ye point out that those studies used only numeric feedback. “We show that when it comes to textual feedback, it should be provided early in the game,” Ye says.

He also comments, “What we find here can very well apply to a traditional context where, say, in an organizational setting, a manager wants a creative solution, or holds a brainstorming session.

“If managers feel that the submissions are converging very quickly, but they want more innovative solutions, they can provide outcome feedback. Or they may observe, ‘Wow, the submissions are all over the place. Doesn’t look like it’s close to what I have in mind.’ Then it’s best to start to provide some process feedback.”

Whichever feedback type they choose, managers should offer it promptly so as to maximize the impact. At the same time, they should be careful to avoid turning their preferences into self-fulfilling prophecies through strongly worded process feedback.

Sanyal uses an illustrative example from his own life: “Many times, if my kids are stuck with something, I hear them and I say, ‘You are on the right track. I won’t tell you the solution, I will only tell you that you’re on the right track.’ So give some overall ideas, but don’t constrain the solution space too much.”

Their work was published in Information Systems Research.

- March 28, 2024

- March 11, 2024

- February 22, 2024

- January 22, 2024

- January 8, 2024