Kirin Emlet Furst, an assistant professor in George Mason University's Department of Civil, Environmental, and Infrastructure Engineering, recently received a National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER Award to investigate how Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are transformed and persist in drinking water distribution systems (DWDS) that bring water to our spigots.

CAREER award funding is reserved for the nation’s most talented up-and-coming researchers. From the NSF website: “The Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Program offers NSF’s most prestigious award in support of early-career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education and to lead advances in the mission of their department or organization.”

PFAS are sinisterly known as “forever chemicals” because once created they do not break down, existing in water and soil—and even human blood—indefinitely. They have been used in numerous applications, including firefighting foams, metal plating, and food packaging, and spread easily through water and air.

This means, whether we like it or not, many of us are gulping down PFAS with every drink of water. To address this, the EPA recently released rules establishing limits on six PFAS in drinking water, affecting approximately 66,000 water systems, serving 90 percent of the country.

“PFAS really like interfaces between water and air and water and surfaces, so they stick to all sorts of stuff,” said Furst. “In DWDS, they may stick to the surface inside pipes and tanks, especially if there is biofilm growth or flaking of the inside material, giving them more to hold on to.” Furst said well-maintained DWDS typically won’t have such issues but knew of one water storage tank that had not been cleaned in 20 years, resulting in three feet of sediment on its floor. Such sediment, along with other conditions, may create conditions for PFAS accumulation and transformation.

The focus of regulators and utilities is removing PFAS at the treatment plant, but in communities where exposure to PFAS is prevalent—near chemical plants, for example—Furst suggests there’s a likelihood that PFAS has been building up downstream, so to speak, in the DWDS.

“In Fairfax County the amount of time water could spend in the distribution system is as long as a week,” Furst said. “In some systems it’s going through miles and miles of pipes, with a lot of places for PFAS to hang out.”

There are more than 12,000 types of PFAS, and in the presence of certain microbial processes, unregulated precursor compounds can be transformed to the more toxic, regulated species like perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Furst worries the new EPA rule, relying on measurements at treatment plants, won’t reflect the levels in water at household taps.

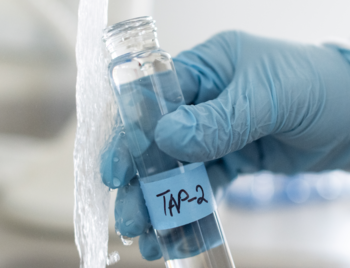

Furst’s lab will get samples from distribution systems from Northern Virginia utilities and she hopes to have a larger DWDS pilot on the Mason Fairfax Campus as part of the “Mason as a Living Lab” program. She hopes her findings will aid in solutions to minimize and mitigate PFAS contamination.

In This Story

Related News

- April 29, 2024

- April 18, 2024

- April 16, 2024

- April 1, 2024

- March 5, 2024